Korean Fantasy Dramas: Love Agents of Socialisation for Romantic Beliefs and Expectations

- Sher Wyn

- Mar 23, 2019

- 43 min read

a 2017 Research Project for University

Abstract

This study is to determine the dominant romantic beliefs and expectations of Korean fantasy dramas viewers as a result of socialisation. The sample for this study is female tertiary students in ---. The quantitate method approach to this study has found that when participants utilised Korean fantasy dramas as a media source to gratify their cognition desires, for diversion, emotional release and social utility, they were enculturated and socialised that they can change a man from a “beast” into a “prince”; that the right mate “completes them”- thus filling their needs and making their dreams come true; and that love overcomes all.

This study has also found that participants are able to maintain a critical distance in their viewing, for they were familiar with the typical storylines and conventions of Korean fantasy dramas. These findings give insight to what are the unhealthy beliefs and expectations of romantic relationships so they can be countered with healthy and realistic ones so that awareness could be raised to the public about unrealistic and unhealthy media portrayals of romantic relationships in the media, especially Korean fantasy dramas, for the public’s individual sustenance of healthy and satisfying romantic relationship.

CHAPTER 1: Introduction

Background of Study

The Korean Wave, commonly termed as ‘Hallyu’, began with the Korean drama First Love, in 1996. Since then, the Wave has slowly but assuredly swept through the media in various regions of the world (Lee, 2011; Chan & Wang, 2011; Miyose, 2015; Ruslan & Latif, 2016). This Hallyu phenomenon has sparked much interest in numerous researchers to analyse how the cultural exports of films, music, food, games (Ruslan & Latif, 2016) influenced the lives of those swept by the Wave in various areas like consumer behaviour (Hsu, 2012), love values (Ho, 2013), and marital intentions (Vu & Lee, 2013).

The international popularity of South Korea’s popular culture began with the release of Winter Sonata in 2002 (Ooi, 2014); the first Korean drama aired in Malaysia (Ruslan & Latif, 2016). Thereafter, broadcast channels in Malaysia have allocated much airtime for Korean programs. In fact, as compared to other foreign counterparts, Korean programs held the largest percentage of airtime (Ruslan & Latif, 2016).

According to Addao (2017), Korean dramas have evolved dramatically over the years from melodramas, to historical dramas, to romantic comedies and presently - to fantasy. However, regardless of the genre, ‘pure love’ and ‘characters’ relationships’ are marked characteristics of Korean dramas (Jiang & Leung, 2012); and love is usually an underlying central theme that will be depicted in idealized ways and that true love lasts forever (Jin & Kim, 2015). In the past five years, there has been a growing popularity with Korean dramas in the fantasy genre. Male protagonists in Korean dramas have undergone a paradigm shift from being humans - Winter Sonata (2002); to an extra-terrestrial being who possess supernatural powers - My Love from the Star (2013); and most recently, to being gods – Goblin: The Great and Lonely God (2017).

My Love from Another Star (2013) was released on international broadcast in numerous countries in Asia – Malaysia, Singapore, Japan, Taiwan, Myanmar, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Philippines (Ooi, 2014) and was named the top television program of 2014 (Baek, 2014). The drama resolves around the romance of a top actress and an extra-terrestrial being with superhuman powers of speed, sight, and hearing (Doo, 2017) who has lived in South Korea for the past 400 years (Baek, 2014). The popularity of this Korean fantasy drama was sensational; the lipstick shade that was rumoured to be used by the female protagonist was sold out at cosmetic shops, even in international duty-free shops (Lee, 2014).

Furthermore, a Chinese man reportedly filed for divorce because of his wife’s obsession towards the FDK whereby she kept comparing him to the male protagonist in terms of romance, looks, and success in life (“Man seeks divorce”, 2014). Researchers have found that individuals who believe strongly in media portrayals of romantic relationships are more dissatisfied with their romantic relationships (Reizer & Hetsroni, 2014; Jin & Kim, 2015). This is because the romantic standards portrayed in the media are used as comparative benchmarks to evaluate their current relationships, which are often unrealistic and unattainable, thus will not measure up the romantic ideals portrayed and observed in the media (Galician, 2004; Reizer & Hetsroni, 2014; Miyose, 2015).

In the Korean fantasy drama Goblin: The Great and Lonely God, to summon the 939-year-old warrior/male protagonist cursed with immortality, who is considered a god; the female protagonist will only need to blow out a flame, whether be it a physical flame, or a virtual flame on a phone application (Doo, 2017). It is vital to note that Goblin attained record-breaking viewership on the Korean cable channel - tvN (“K-drama Goblin”, 2017; Vannelli, 2017); it also broke previous records of other drama series. In terms of content power index (CPI), an integrated index used to measure the popularity of television programs (Fry, 2015 & Lee, 2017), Goblin had a score of 7,449 as compared to another highly popular Korean drama Descendants of the Sun (2016) that has a score of 5,518 points at its peak (Ferrer, 2016). Korean dramas have been found to be highly appealing and popular amongst young females in their teens and in their young adult years, with their ages ranging from 14 to 30 years old (Jung, 2010; Jin & Kim, 2015; Miyose, 2015; Ruslan & Latif, 2016). This age group are known for their interest in the concept and pursuit of love (Hendrick & Hendrick, 2002; Hetsroni, 2012; Lee; 2012) and they are also the very ones who would be susceptible to be influenced by media portrayals (Galician, 2004; Miyose, 2015).

Pop culture critic Jung Duk Hyun’s commented that "Goblin has gone a step further in conjuring an ideal knight-in-shining armour. We've evolved past god-like men to actual gods, who don the appearance of good-looking human men. The popularity of the character can be attributed to female viewers’ yearning for all-powerful male figures who can solve the problems of modern women’s increasingly stressful lives,” (Doo, 2017). It is easy to escape to a world where someone will come to one’s side and provide everything immediately, with no questions asked. However, that should not be expected from real-life relationships (Doo, 2017). However, this is usually what is portrayed in television programs such as Korean fantasy dramas. In actuality, two individuals with their own identities are to complement each other and work together as equal partners towards common life goals (Galician, 2004).

Problem Statement

Presently, divorce rates around the world are one the rise (Røsand, Slinning, Røysamb, & Tambs, 2014; Lakshiny, 2016; Kamini, 2016; Mokwape, 2017; Serie, 2017). According to Kamini (2016), the divorce rate in Malaysia is escalating; there was an increase from 6,573 to 9,020 divorce cases between 2008 to 2012 among non-Muslim couples. Furthermore, based on the latest available statistics from JAKIM, Malaysia’s Department of Islamic Development, seventy-seven Muslim couples dissolve their marriages daily (Kamini, 2016). Røsand et. al (2014) found that one leading factor for divorce, on part of the woman, is dissatisfaction with the relationship. Other contributing factors include incompatibility (Lakshiny, 2016), differences of opinion, family (e.g. involvement of the in-laws) and as well as finances (Kamini, 2016).

Researchers have found that television programmes, like Korean fantasy dramas, are strong influencers on the romantic beliefs and expectations of viewers (Holmes & Johnson, 2009; Jin & Kim, 2015) because they perpetuate portrayals of romantic relationships that are unrealistic and unattainable (Miyose, 2015). Given that the core area of this study is on the socialisation of romantic beliefs and expectations through the portrayals of the nature of romantic relationships in Korean fantasy dramas, it is vital to define what is meant by ‘realistic’ and ‘unrealistic’. Being ‘realistic’ is associated with having factual and empirical evidences – those that are observable and documentable. Being ‘unrealistic’ is associated with having illusions, fantasies, idealisms, or unattainable perfection that sets a standard that which people might ‘strive for but not arrive at’ (Galician, 2004).

It is the portrayal of what is ‘idealistic’ as ‘typical and real’ that makes media images influential yet harmful for viewers, who will utilise those benchmarks to evaluate the quality of their romantic relationships (Reizer & Hetsroni, 2014; Miyose, 2015). Osborn (2012) found that belief in television portrayals is a stronger predictor of individuals’ romantic expectations and assessment of their romantic relationships as compared to the time spent viewing romantically themed programs.

Hence, to ensure that the current and the future generation build and sustain healthy and satisfying romantic relationship, it is vital for them to be socialised realistic and practical relationship expectations so that they will enter the relationship with the proper mind set, beliefs and expectations; and enjoy healthy romantic relationships.

Research Objectives

The purpose of this study is to gain knowledge on what are the dominant romantic beliefs and expectations of Korean fantasy dramas viewers as a result of socialisation. The findings of this research gives insight to what are the unhealthy beliefs and expectations of romantic relationships so they can be countered with healthy and realistic ones. Also, the research findings could be used to raise awareness to the public about unrealistic and unhealthy media portrayals of romantic relationships in the media, especially Korean fantasy dramas, for the public’s individual sustenance of healthy and satisfying romantic relationship.

Research Objective 1: To investigate the degree of viewers’ involvement with Korean dramas in the fantasy genre.

Research Objective 2: To determine the dominant romantic beliefs and expectations of Korean Fantasy drama viewers.

Research Questions

This study will answer the following questions:

Research Question 1: How does viewers use Korean fantasy dramas as agents of socialisation?

Research Question 2: What are the dominant trends of romantic beliefs and expectations viewers’ have developed through the watching of Korean fantasy dramas?

Significance of Study

There is a scant amount of studies that focus on what individuals learn about love through the consumption of media (Holmes & Johnson, 2009) and on the effects of mass media on individuals’ romantic beliefs and expectations although one’s romantic relationship is critical to one’s happiness and well-being (Jin & Kim, 2015).

Hence, given that Korean fantasy dramas have not been studied due to its recent popularity, this study analyses Korean fantasy dramas as an agent of socialisation on a young population whose beliefs and expectations are highly susceptible to be influenced by media portrayals. Specifically, this study examines the contribution of Korean fantasy dramas as a source of information and influence on the beliefs and expectations about romantic relationships for female students in ---.

Television critics have raised concerns about the negative effects of these Korean fantasy dramas on its copious viewers. Consequently, it is imperative to analyse Korean fantasy dramas critically so that more knowledge can be gained to counter unhealthy and unrealistic beliefs and expectations about romantic relationships that are portrayed in Korean fantasy dramas.

This study would also add to previous literatures on the study hegemonic portrayals of romance and love by taking on Osborn’s (2012) recommendation to utilise the uses and gratification theoretical framework to fill in research gaps of studies that took on the cultivation framework. Also, as proposed by Miyose (2015) for future research, this study took into account the viewers’ media literacy skills and how it affects the way viewers interpret Korean dramas’ hegemonic portrayals of romance and love, which influences future romantic relationship and divorce trends.

CHAPTER 2: Literature Review

Uses and Gratification Theory as a Theoretical Framework

The uses and gratification theory (UGT) is an audience-entered approach to understand mass communications. Instead of asking ‘what do media do to people’, UGT asks ‘why do people use media and what do they use it for’ (Katz, Blumler, & Gurevitch, 1974; McQuail, 1983). It suggests that people are aware of their own needs and thus are able to verbalise them. It also posits that consumers are proactive in their selection and usage of media in that they actively assess the available media and select the media that would satisfy their needs and gratify them (Hasan, 2015). In the same vein, the model for UGT proposes that the consumer-audience have needs and drives that are satisfied by using both media and non-media sources. Media related sources of uses and gratification can be classified into the six categories of cognition, diversion, social utility, affiliation, expression, and withdrawal (Dominick, 2013).

An individual is using media in a cognitive way when he or she uses a mass medium to gain knowledge about something; whether is it using media to keep up with current events or to learn about things in general. It is using media to satisfy one’s desire for general knowledge, to learn things never done before, to satisfy one’s curiosity, to gain new insights and ideas (Dominick, 2013).

Diversion refers to human nature’s need for stimulation, relaxation, emotional release; for an escape from routine and problems (McQuail, Blumber, and Brown, 1972; Severin & Tankard, 2001). Stimulation is the inherent motivation of humans to seek emotional and intellectual stimulation to maintain a minimum level of intellectual activity. The media has leveraged upon this to help individuals avoid boredom in various ways – audio-visual entertainment in aeroplanes and grocery carts, magazines at waiting rooms, and advertisements various locations.

Researchers have also found factors like nice fast-paced plots with happy endings or touching storylines, production quality, nice music, beautiful scenery, excellent cinematography, fashionable actors and actresses, to be the main reasons that make Korean dramas so appealing and popular (Kwon, 2006; Chan & Wang; 2011; Hogarth, 2013; Ruslan & Latif, 2016).

The aforementioned factors demonstrate the relationship between the ‘feminine viewer-consumer’ and television; meaning these are the very factors that appeal to the female viewer and consumer’s senses and psyche (Joyrich, 1996; Lee, 2012). Morever, Chan and Wang (2011), Ruslan and Latif (2016) have also found that young female viewers liked Korean dramas for the ‘sensitive male characters who were willing to sacrifice everything for their love’ (Chan & Wang, 2011, p. 294; Lee, 2012), who serves as diversion from mundane chores and a temporary escape from reality and the pressures of school and the workplace. However, these viewers are able to maintain a critical distance in their viewing for they are familiar with the conventions of Korean dramas (Chan & Wang, 2011).

Relaxation is the escape from the daily problems and pressures of human’s existence. When too much information or stimulation is present in an environment, it can affect humans negatively; it is important to seek relief from this sensory overload. In Chan & Wang’s (2011) study, watching Korean dramas is a form of relaxation for a respondent because of the ‘predictable-thus-stress-free’ plots when compared to programmes like the American television series ‘Survivor’, where scheming against each other is a major part of the show that reminded the respondent of office politics.

Emotional release, also known as catharsis, is a complex manifestation of diversion (Dominick, 2013). It can take the obvious form of horror movies where people screamed their lungs out, or tearjerkers where people cried their eyes out. Or it can also take the subtle form of soap operas where viewers are comforted by identifying with fictional characters portrayed in the media, or by seeing that these characters having troubles greater than their own. Individuals also could participate vicariously in media characters triumphs, tragedies or frustrations that resemble the everyday life.

Social utility refers to the function of media that addresses and fulfils the human need to build, maintain and strengthen relationships with family, friends and others in society (Dominick, 2013); it is using media socially. The media provide a common ground for topics of discussions and social conversations where it is used as conversational currency when individuals strike up conversations about movies seen, books read, songs heard (Dominick, 2013); it is socially useful to have a large repository of things to talk about. The media can also be used as a means to overcome feelings of loneliness or identification whereby feelings of friendship and kinship (parasocial relationships) is formed with media characters (Dominick, 2013). Jin and Kim (2015) posits that as compared to males, females watched more television drama and had more parasocial interactions than males. It was found that parasocial relationships mediated the effect of drama viewing on romantic belief, rather than the time spent watching dramas (Osborn, 2012; Jin & Kim, 2015). Those who viewed more television dramas had higher levels of parasocial interaction, which lead to stronger romantic beliefs (Jin & Kim, 2015).

Korean Fantasy Dramas as Agents of Socialisation.

Socialisation, one of the functions of mass media, is the process individuals learn the important norms, behaviours, values, and culture of their society through agents of socialisation like the mass media (Galician, 2004; Dominick, 2013). By the time an individual is eighteen years old, except for sleep, one would have spent more time viewing television than any other activity (Dominick, 2013). According to McLuhan (as cited in Galician, 2004), ‘the dominant medium of a society in any given time is the main agent of social change, altering the way people process information and think about the world’ (p. 26 – 27). The media maintains the status quo that is created by the dominant group’s ideas, thus making media hegemonic (Galician, 2004). For example, on hegemonic notions of love and romantic beliefs, Hefner and Wilson (2013) posits that media portrayals sets the expectation on how relationships forms, develops, functions, and is maintained. Therefore, in view of the Korean Wave phenomenon, television programmes like Korean fantasy dramas are powerful socialisation agents from which people earn values and model behaviours.

A simple way to describe any act of communication and/or transmission of information - is through answering these questions of Laswell’s Communication Model: ‘Who? Says what? In which channel? To whom? With what effect?’ The scientific study of the communication process concentrates upon one or another of the aforementioned components (Lasswell, 1948). In communication theory, ‘who’ refers to ‘the sender’ – usually a team of professional communicators within a media institution like a television network (Laswell, 1948; Galician, 2004); or like in this study, the scriptwriters and producers of Korean fantasy dramas. The sender usually has a combination of three basic reasons for sending messages – to educate, to entertain, and to persuade; with one of it being the dominant one. In fulfilling these functions, it serves the larger function of transmitting the culture and socialising the public (Galician, 2004). While studying the impact of soap operas, researchers (Rubin, 1985; Carveth & Alexander, 1985; Perse, 1986; Perse & Rubin, 1988; Fink & Galician, 1996) found that viewers were more likely to embrace the values and messages when their purpose for viewing were for enjoyment or out of boredom rather than for goal orientated purposes like character identification. In other words, viewers learnt more when they were not seeking information.

Petty and Cacioppo (1986) posits that individuals would be more influenced by entertaining messages in the Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. According to the model, there are two major pathways of persuasion, the central route and the peripheral route. In the central route, individuals would be on the alert and their analytic mode; hence having difficulty reaching them. In the peripheral route, however, individuals would be relaxed and have their defences down; that is where messages packaged with entertainment would have the most influence without the audience realising that they have been enculturated, until much later. According to Baran (2002, p. 374), it is difficult to change enculturated notions, even when individuals know better or sincerely want to change.

‘What’ is the message the sender wants to share; another mass communication term for ‘message’ is ‘content’. Messages and content are constructed and given meaning to by using symbols like words and pictures (Galician, 2004). Researchers have highlighted cultural proximity as the overarching reason for the popularity of Korean dramas (Kwon, 2006; Chan & Wang, 2011; Schulze, 2013; Ruslan & Latif, 2016) whereby viewers are drawn towards Korean dramas because of the Asian sentiments embedded and affected by Confucian emphasis on respect, filial piety and family values (Schulze, 2013). In this vein, Lee (2012) found that the function of conflicts in Korean dramas is to transmit ethical messages.

‘Channel’ refers to the medium or the vehicle of mass communication, like the television, movies, and certain aspects of the Internet; technological devices that enable the sender to reach a large audience (Galician, 2004). The medium itself has a direct impact on how individuals and society think and act, it doesn’t just merely transmit a message or content (McLuhan, 1964). Researchers recognize the value of studying a genre that has a devoted audience over the years (Perse, 1986). In that respect, it is fitting to study the phenomenon of the fantasy genre for Korean dramas as it is highly popularly among viewers from different media sources like television, steaming online videos, and DVDs (Lin & Kwan, 2005; Shim, 2006; Jiang & Leung, 2012; Schulze, 2013; Ruslan & Latif; 2016).

‘Whom’ refers to the mass, diverse and large audience or receivers. Studies have found that the demographic of the Korean Wave consumers varies with countries; for example, consumers from Japan is mostly made up of middle-aged women who regarded the content of Korean dramas as nostalgic, while Chinese consumers consist of those from the younger generation, aged 30 and below, who are keen to consume and model after portrayals in Korean dramas (Mori, 2008; Iwabuchi, 2008; Jung, 2010; Yang, 2012; Ruslan & Latif, 2016). There is no guarantee, however, that a sent message will be received and decoded as the sender intends, which brings us to the last component – ‘effect’.

In communication theory, synonyms for ‘effect’ are impact, influence, and consequence. The receiver will always be affected, however slightly. The effect could be a combination of cognitive (a perception or thought), affective (value or emotion), or behavioural (an action). One example of effect is feedback, where roles are switched between the sender and the receiver - the sender becomes the receiver, and the receiver becomes the sender. Feedback tells the sender how the message was received and enable the sender to refine the message for the audience of receivers (Galician 2004). For instance, a website exists for every Korean drama where producers post the synopsis of the dramas and fans are able to provide their feedback. If the fans do not like the ending of a Korean drama and protests too much, producers would actually modify and reshoot the ending to appease the fans by fulfilling their demands (Chan & Wang, 2011; Schulze, 2013). It is important to note that effects are not always what the sender intends because the effects are often dependent on the psychological filters (biases) that regulate individual’s selective exposure, perception and retention (Galician, 2004). Individuals prefer to seek out idea and information that are consistent with their own beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours and tend to avoid communication that are inconsistent (Wilson & Wilson, 2001).

In essence, for the purpose of this study, ‘who’ refers to the scriptwriters of Korean fantasy dramas; ‘say what’ refers to the unrealistic portrayal of romantic beliefs and expectations in Korean fantasy dramas; ‘in which channel’ refers to the the Korean fantasy dramas; ‘to whom’ refers to the female participants of this study; ‘with what effect’ of refers to the effects of Korean fantasy dramas as agents of socialisation on love.

Love, K-Dramaland and Galician’s Mass Media Love Myths

In 2012, the most searched phrase on Google was – ‘What is love’ (Al-Kalili, Perry, Baggini, Moyes, & Wybourne, 2012). In an attempt to answer this question, writers from an array of disciplines were gathered to give their definitions of the much pondered phrase - to the physicists, love is chemistry; to the psychotherapist, love has many guises; to the philosopher, love is a passionate commitment; to the romantic novelist; love drives all great stories; to the nun, love is free yet binds us (Al-Kalili, Perry, Baggini, Moyes, & Wybourne, 2012).

According to Yale psychology and education professor Robert J. Sternberg (1987, 1998), a prolific and respected scholar on the subject of love, there is no single definition that describes love across cultures or throughout the ages. Love means different things to different people at different cultures and historical periods. Even though poets, philosophers, theologians, have been investigating the nature of love for centuries; in the scientific field, love research is relatively new in the wide array of disciplines, like social and behavioural psychology, sociology, human and mass communication, that now examines love (Galician, 2004). However, ‘Love Is A Story’ is one definition of love by Sternberg that fits the context of mediated messages about love.

Love, in Korean dramas, is the most cherished value and is the factor that impels the plot forward (Lee, 2012). Korean dramas are hinged on elements like ideal love, ideal characters, and ideal human relationships, of which are fantasies – wishful thinking that are not realistic (Lee, 2015). Korean dramas, or ‘K-Dramaland’, provide audience with the illusion of perfect love and family without having them to change reality and in that help them to forget their frustrations with reality, no matter how briefly (Lee, 2012). A pure, sincere type of love and the goodness of human beings is promulgated in the way conflicts are unravelled in Korean dramas. The courses of conflict and conflict resolution follows a customary rather than a logical path (Lee, 2012). ‘K-Dramaland’ is an emic term that was coined by international fans to refer to the imagined world of Korean dramas created through the collective work of its writers, directors, actors, and viewers. It refers to ‘a fictive world that represents a self-contained universe’ (Schulze, 2013, p. 369) where occurrences, characters’ behaviour and reaction, are understood and questioned according to a set of clichés or laws of its universe (Schulze, 2013).

Miyose (2015) found that a few common themes of Westernised ‘status quo’ love can be observed in K-dramaland by employing Galician’s (2004) myths of hegemonic portrayals of romantic relationships in the mass media. Myths are stories that bring the ancient past to the postmodern present because of the universal appeal of their morals, which have socialised society throughout the ages (Vande Berg, Wenner, & Gronbeck, 1998). They are the stories that determine a society’s perspectives about themselves, about the world, and about what behaviours have meaning. Truths can be communicated through myths, thus making it a great teaching tool; however, it can be beneficial or detrimental as it can control or enslave us. As a central force in socialisation, myths always have a moral force that are conveyed piecemeal through legends, folk tales, and epics (Galician, 2004).

The first of Galician’s (2004) mass media love myth states, ‘Your perfect partner is cosmically predestined, so nothing and/or nobody can ultimately separate you.’ This myth states that love is predestined, that there is someone out there for everyone and fate will bring two individuals who are destined to be lovers, together, at the right time. The implication of this theme is that individuals would overlook the idea that conflict management is a core component of a successful relationship (Gottman, 1999) and that if the relationship did not last, it is because it is not meant to be (Miyose, 2015).

The second love myth suggests that, ‘There’s such a thing as “love as first sight”’ (Galician, 2004) or in romantic comedies, “hate at first sight” (Miyose, 2015). In K-dramaland, the male protagonist’s family usually pairs him with a rich and beautiful female from his own social class. He does not have any attention for her, instead he is loyal to his lover, the female protagonist who is from a lower social class, whom he probably fell in love, or sometimes hate, at first sight (Lee, 2012).

The third love myth states, ‘The true soul mate should know what you’re thinking or feeling (without your having to tell)’ (Galician, 2004). According to Eidelson and Epstein (1982), this third myth, ‘mind reading is expected’ is identified as one of the five dysfunctional relationship beliefs that is common among couples who seeks counselling; it is linked to decreased relationship satisfaction and is detrimental to the quality of romantic relationships (Bradbury & Fincham, 1987; Baucom & Epstein, 1990; Kurdek, 1992; Baucom et al, 1996).

The fourth myth suggests that ‘If your partner is truly meant for you, sex is easy and wonderful.’ However, due to the conservative Confucian societal context, unlike Western media, physical intimacy is usually suggested but not depicted (Chan & Wang, 2011; Ruslan & Latif, 2016). This Korean culture’s preference for sexual purity in women is reinforced in K-Dramaland visually, where actresses who has a pure, fresh, and lovely image would be casted (Lee, 2012). Also, female protagonists are usually passive and self-denying; and they are usually portrayed as good, kind, faithful, cheerful, persistent, assertive, competent, and courageous (Lee, 2012). This illustrates the fifth of Galician’s (2004) love myth – ‘to attract and keep a man, a woman should look like a model or a centrefold”, in the Korean cultural context. In other words, this myth perpetuates the idea that in order to attract a man, the woman needs to look attractive.

Love is difficult to realize in K-Dramaland because the lovers who have strong mutual love and desire are usually individuals who have conflicting sociocultural values or are of two different classes (Lee, 2012; Miyose, 2015). The female protagonist is most often from the lower or middle class and the male protagonist from the upper class (Lee, 2012). This is another myth that is promulgated in K-Dramaland, that “the man should not be shorter, weaker, younger, poorer, or less successful than the woman” (Galician, 2004), which instils the idea that the man has to be more powerful and domineering than the woman. Male protagonists in K-Dramaland are typically professionals from wealthy families. They are usually stereotyped to be intellectually and physically competent, psychological determined, charismatic, decisive, courageous, trustworthy, and due to an emerging demand - warm, sensitive, and gentle; however, the two most prevalent traits attributed male protagonists in K-Dramaland are economic and intellectual power (Lee, 2012).

A love myth constantly portrayed in K-Dramaland is ‘the love of a good and faithful true woman can change a man from a “beast” into a “prince”’ (Galician, 2004). According to Miyose (2015), this depicts the idea that love has the power to transform individuals in a relationship and suggests that the love couples have for each other will surpass their individual differences. It forgoes the idea that individuals should find a compatible partner with similar goals and values. It also sets the expectation that individuals need to change for a relationship to work (Galician, 2004). In K-Dramaland, it is a common theme whereby the male protagonist’s egotistical behaviour and stone cold heart is made warm by the female protagonist, who is loving, empathetic and courageous. This is usually showcased by having the male protagonist being a challenge to the female; whereby she proves that she is virtuous by having the ability of loving him although he has terrible attitudes. However, as time progresses, the male protagonist undergoes an attitude transformation to be more thoughtful, kind and caring because of her love (Lee, 2012; Schulze; 2013; Miyose, 2015). This myth can influence individuals to remain in abusive relationships with the thought that the other individual will become better if he or she were to love continually (Miyose, 2015). Most often, women are the ones most at risk of this abuse constantly because they are left to think that it is her fault that her partner is the way that he is (Galician, 2004); and puts the burden on the herself instead of man himself to change his attitude (Miyose, 2015).

Relationship grows when romantic partners have mutual respect for each other and share the same or similar values; if not, conflict would ensue. This is where another relationship myth is often perpetuated in K-Dramaland – “bickering and fighting a lot means that a man and a woman really love each other passionately.” This sheds an unrealistic and unhealthy romantic light on on having constant conflict in a relationship due to varying individual values and lifestyle of the male and female protagonists, which is detrimental to any long-term relationships (Galician, 2004; Miyose, 2015). In contrast, Eidelson and Epstein (1982) found the belief of “disagreement is destructive” to be dysfunctional and detrimental to one’s relationship quality and is linked to decreased relationship satisfaction.

With the love myth “all one really need is love, so it doesn’t matter if one or one’s lover have very different values , Galician (2004) asserts that the mass media usually portray people with different lifestyle and values easily functioning as a couple; and that the post-courtship stage is rarely portrayed. This is because it is unexciting to depict realistic romantic relationships and to portray homogamy - marriage between people from similar sociological or education background. According to Miyose (2015), K-Dramaland’s couples are usually incompatible with each other; that is, they usually have differing social status and values. However, this dissimilarity is often disregarded because such romantic relationships is portrayed to remain intact because love is the single most cherished value and desire. Although the female protagonist often has multiple desires, such as to be successful in her career, to save or reunite with her family; love is the most important desire of the protagonist, and love acts as the factor that impels the plot forward (Lee, 2012).

Love that is depicted in K-Dramaland is pure, loyal, immutable and undying rather than what it really is - illusive, mutable, and vicarious (Chan & Wang, 2011; Lee, 2012). Lovers adhere to their love adamantly no matter how unfavourable the circumstances are (Lee, 2012). Among the impediments that always frustrate and delay love are family, illnesses, the plotting of rivals, misfortunes. The difficulties of realising love send the message that love is important. The more challenging it is to actualise love, the more the audience longs for the realisation of it (Lee, 2012). For instance, if the protagonists were to ever consider giving up on love, the only reason would be for the sake of each other, but eventually at the end of a drama series, their love would be a miraculous resolution of hurdles to their love and their love would be realised (Lee, 2012). Females are said to more relationship-orientated than men, and that when they are frustrated by reality’s struggles with love and family relationships, the ideal men, sublime love, and miraculous resolution of life’s struggles to be comforting (Lee, 2012). On this note, Galician (2004) contended that though short-termed relationships with individuals who are incompatible may seem exciting, ultimately, for a relationship to flourish and be long-term, the foundation of romantic relationships has to be built on similarities.

The last myth that addresses how love is portrayed in K-Dramaland, is ‘The right mate ‘completes you’ – filing your needs and making your dreams come true.’ The drawback of believing this myth is that it leads individuals to place unrealistically high expectations on one’s partner to satisfy their need and overcome any hindrance (Galician, 2004) when realistically, an individual can take charge of their own lives and cultivate their own completeness. In K-Dramaland, the female protagonists would usually be depicted as independent, strong, and caring when they are single (Hogarth, 2013). However, after getting into a relationship, they would usually transform to be totally reliant on the male protagonist (Miyose, 2015). In the content analysis of Korean dramas in the flower boy genre by Miyose (2015), it was found that whenever the female protagonist is in trouble, the male protagonist would use his abilities to come to the rescue. This suggests that women will always need a man to come to their rescue and that they are not able to rescue themselves from various life situations. In addition, the male protagonist is usually successful at the things that they do while the female protagonist would constantly be struggling to just make a living or to get by each day. The male protagonist does not need help to achieve his goals but for the female protagonist, without help from the male protagonist, she cannot succeed (Hogarth, 2013; Miyose, 2015). This confirms the concern raised by another culture critic, Ha Jae-guen, who said "With these abilities, the male becomes a saviour of sorts to the female. Female viewers find comfort in these characters. But their very support of such characters could lead to a decline in women's social status," (Doo, 2017).

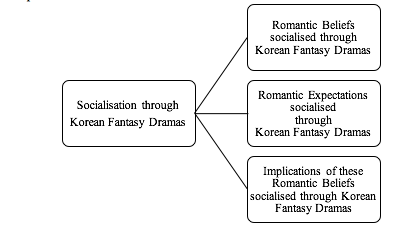

Conceptual Framework

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework

Korean fantasy dramas can function as agents of socialisation for individuals to learn important norms, values, behaviours and cultures. The Uses and Gratification Theory (UGT) posits that individuals are proactive in their media selection where they would select media that would satisfy their needs and gratify their human desires. In engaging with any of the six media related sources of uses and gratification – cognition, diversion, social utility, affiliation, expression, and withdrawal (Dominick, 2013) individuals would be socialised and persuaded because the aforementioned elements function alongside the peripheral route in Petty and Cacioppo’s (1986) Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion.

Viewers of Korean fantasy dramas are susceptible to the romantic beliefs and expectations because these messages on romantic beliefs and expectations are packaged with entertainment thus enculturating the viewers without their realisation (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Enculturated notions are difficult to be changed (Baran, 2002) and can have serious implications especially if these notions of romantic beliefs and expectations are unrealistic and unattainable.

CHAPTER 3: Methodology

Method

As the purpose of this study is to determine the dominant romantic beliefs and expectations - so that unrealistic romantic notions can be countered with realistic ones in future educational settings and/or through future films, the best suited approach is the quantitative survey. The nature of this study requires hard data, statistics and figures; hence, the quantitative survey research method provides the possibility to measure the reactions of sample group with a limited set of questions (Wimmer & Dominick, 2014; Berger, 2014). There will also be a better precision in result reporting because the questionnaire is standardised. Most importantly, a survey can quantify the features of social reality (Wimmer & Dominick, 2014; Berger, 2014).

The purposive method was employed for this study because of the niche nature of this study. Purposive sampling targets the group of people who can provide the desired information because they are the only ones who have the information and/or qualify for the criteria set by the researcher (Sekaran, 2006; Creswell, 2012; Crossman, 2017). To qualify for this study, participants must be a female student in --- and, she must have watched at least two out of the eight Korean fantasy dramas listed in the questionnaire.

This cohort of information-rich participants was selected because they are known for their interest in Korean dramas and in the concept and pursuit of love (Hendrick & Hendrick, 2002; Hetsroni, 2012; Lee; 2012) and thus would contribute to this study of romantic beliefs and expectations. Those who failed to meet the aforementioned criteria were omitted from the study.

Data Collection Procedure

A total of 100 female tertiary students in --- participated in this study. This research utilised Google online survey form and hardcopy version where the purposive sampling method was employed. A total of 29 responses were garnered online through a hyperlink to an online survey form; 80 other respondents were approach purposefully around ---. However, nine participants’ responses were omitted because, in one way or another, they did not meet the research study’s criteria.

Instrument Design

In this study’s quantitative survey, participants answered four demographic questions pertaining to their age, sex, relationship status and level of study in --- followed by one checklist qualifying question where they indicated, from a list of eight Korean fantasy dramas, at least two Korean fantasy dramas that they have watched. This is to condition the respondents to reflect on the Korean fantasy dramas they have watched as they answer the rest of the survey.

Then, they responded to a total of thirty-two statements on five-point Likert scales (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree) that were categorised into three sections. The first section under ‘Socialisation’ consist of nine items, the second section under ‘Romantic Beliefs and Expectations’ consist of another nine items, and the last section, also categorised under ‘Romantic Beliefs and Expectations’ consists fourteen items. The Cronbach’s alpha for this study is 0.878.

Socialisation.

To probe Research Question (RQ) 1 – ‘how does viewers use Korean fantasy dramas as agents of socialisation’, Zurbriggen and Morgan’s (2006) Reality Dating Television Program’s Viewer Involvement Scale was adapted. The scale is made up of items like ‘Korean fantasy dramas inspire me to experience new cultures’, ‘Watching Korean fantasy dramas make me want to be in a serious relationship’, and ‘I talk about Korean fantasy dramas in conversations with others.’

Romantic Beliefs and Expectations.

To probe RQ2, two sets of questionnaires were used to determine the dominant romantic beliefs and expectations of the participants. The first set of questionnaire was adapted from Galician’s (2000) Dr. FUN’s Mass Media Love Quiz (Scale 1). Participants responded to nine items like ‘My perfect partner is cosmically predestined, so nothing/nobody can ultimately separate us’, ‘The love of a good and faithful true woman can change a man from a “beast into a prince”’, ‘The right mate “completes you” – filling our needs and making your dreams come true”.’

The second set of questionnaire was adapted from Sprecher and Mett’s (1989) Romantic Belief Scale (Scale 2) to measure the ideology of romanticism. Participants responded to 14 items like ‘If I were to be in love with someone, I would commit myself to him even if my parents and friends disapprove of the relationship’, ‘I’m sure that every new thing I learn about the person I choose for a long-term commitment will please me’, and ‘If I love someone, I know I can make the relationship work, despite any obstacles”’.

Data Analysis

The data collected was processed using the Google online survey form, Microsoft Excel, and the ‘Statistical Packages for Social Sciences’ (SPSS) software. Responses from the paper questionnaire were manually filled in to the Google online survey form. Then, the Microsoft Excel document of the collated data was downloaded and copied to the columns of the variables’ formulated in SPSS accordingly.

Descriptive analysis was undertaken to analyse the characteristics of the variables of interest (i.e. socialisation, romantic beliefs, romantic expectations) as this form of analysis would be able to describe the variables well by offering a detailed profile of them. According to Sekaran (2006), the goal of a descriptive study is to describe relevant aspects of a phenomenon of interest whereby vital information would be made available before taking any corrective action (e.g. countering specific unrealistic romantic beliefs and expectations through education or films). Furthermore, the data processed through descriptive analysis will aid in the understanding of the variable’s characteristics better, to think systematically about the variables, to offer ideas for further probing and research, and to make decisions regarding the information discovered (Sekaran, 2006).

CHAPTER 4: Findings & Discussion

Participants

The participants of this study were 100 female undergraduate students in ---. Participants’ age range from 17 to 24 years old (M = 20.36, SD = 1.514).

Participants enrolled in pre-university programmes made up 24% of the sample, 3% of participants were in diploma, 63% in degree programmes, and 10% in professional accounting programmes. Those who have never been in a relationship made up 44% of the sample, 25% is currently in a relationship, and 31% had been in relationship(s), none of them were married.

Qualifying Factor

The qualifying factor for this research is that respondents must have watched at least two of the eight Korean fantasy dramas listed. 34% of the respondents of this study have watched two Korean fantasy dramas, 22% have watched three, 18% have watched four, 14% have watched five, 9% have watched six, 1% have watched seven, and 2% have watched all eight of the Korean fantasy dramas listed.

The three most watched Korean fantasy dramas among the 100 research participants are Goblin: The Great and Lonely God (M = .69, SD = .465), followed by The Legend of the Blue Sea (M =.65, SD =.479), and My Love from Another Star (M =.63, SD =.485) (see Table 1). This reflects and affirms the popularity of these Korean fantasy drama. These dramas all have mythical or legendary undertones, and thus have underlying socialisation forces of morals, values, ideals, and beliefs they are conveyed piecemeal through legends, epics, and folktales (Galician, 2004). As a recap, the Korean fantasy drama Goblin is a love story about an ancient warrior who became a Goblin, also known as a ‘Dokkaebi’, and his destined ‘Goblin’s bride’ who is a senior in high school. ‘Dokkaebi’ are legendary creatures from Korean folkore and mythology who possess extraordinary abilities and powers. In Goblin, the female protagonist needs only to blow out a flame, whether physical or virtual, to summon him for help, wherever she may be (Doo, 2017). The Legend of the Blue Sea, is a love story between a town head and a mermaid in the Joseon era (the Korean kingdom from 1392 – 1897) their love story is juxtaposed with their reincarnations in the present world. My Love from Another Star is a resolves around the romance of an extra-terrestrial being with superhuman powers who has lived in South Korea for the past 400 years and top actress (Doo, 2017). These love story have the element of juxtaposition of their Joseon era lives and their modern day reincarnations where the lovers are once again reunited.

Socialisation

Socialisation is the process individuals learn the norms, behaviours, values and culture of their society (Galician, 2004; Dominick, 2013). Seventy-eight cumulative percent of the 100 participants agree to ‘Korean fantasy dramas inspire me to experience about new cultures’ (M=3.98, SD=0.985) and fifty-six cumulative percent of participants agree to ‘Korean fantasy dramas inspire me to try new things’ (M=3.38, SD=1.090)(Table 4). UGT posits that an individual is using media in a cognitive way when one uses media to learn things never done before and/or satisfy one’s curiosity and desire to gain knowledge, insights, and/or ideas. These desires to experience new cultures and experience new things can be attributed to several elements that makes Korean dramas appealing - beautiful scenery, excellent cinematography, fashionable characters. These elements can also be classified under the diversion/stimulation category of UGT where humans inherently would seek emotional and intellectual stimulation to maintain a minimum level of intellectual activity. This can be linked to the Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), whereby the peripheral route is the most effective way of transmitting messages because messages and values packaged with entertainment has the most influence without the audience realising that they have been enculturated. Baran (2002), posits that it is difficult to change enculturated notions, even when individuals know better or sincerely want to change. On a similar note, researchers have found that viewers of soap operas learnt more and were more likely embrace and be socialised by values and messages (e.g. Confucian values) when enjoyment was the purpose for viewing rather than goal orientated purposes (e.g. seeking information) (Rubin, 1985; Carveth & Alexander, 1985; Perse, 1986; Perse & Rubin, 1988; Fink & Galician, 1996).

As evidenced in Table 3 and 4, Korean fantasy dramas is utilised by participants more for the sake of enjoyment rather than goal oriented purposes. Forty-three cumulative percent agree that ‘Korean fantasy dramas help me learn from the mistakes of others’ (M=3.2, SD=.985), thirty-five cumulative percent agree that ‘I learn about the opposite sex from watching Korean fantasy dramas’ (M=3.06, SD=.952), twenty-seven cumulative percent agree that ‘Korean fantasy dramas help me learn how I’m supposed to act in different situations’ (M=2.9, SD=.905).

Moreover, Korean fantasy dramas is also utilised by participants as a conversational currency, an element under the social utility category in UGT, when seventy cumulative percent of them agree that ‘I talk bout Korean fantasy dramas in conversations with others’ (M=3.82, SD=1.029). Social utility refers to the function of media that addresses and fulfils the human need for interaction and forming close connections with others in society.

Besides, forty-three cumulative percent of participants agreeing that ‘Korean fantasy dramas give the wrong messages about relationships’ (M=3.27, SD=1.024) is evidence that participants utilised Korean fantasy dramas as a means for a temporary escape from reality and/or relaxation, another category under the classification of diversion in UGT, thus enabling them to maintain a critical distance in their viewing because of their familiarity with the conversions of Korean fantasy dramas. In the similar vein, forty-seven cumulative percent agree that ‘Watching Korean fantasy dramas make me want to be in a serious relationship’ (M=3.28, SD=1.181), but twenty-four cumulative percent of participants agree that ‘Watching Korean fantasy dramas make me want to get married’ (M=2.73, SD=1.118). This could be due to the participants’ age that ranges from 17 years old – 24 years old; they are at the age where they are interested in love but not in marriage they are all tertiary students and are also not at the present day’s conventional age to be married.

Romantic Beliefs & Expectations

Miyose (2015) posits that several themes of Westernised status quo love can be observed in K-dramaland, an emic term coined to described the imaginary world of Korean dramas that operate with its own self-defined laws, by employing Galician’s (2004) myths of hegemonic portrayals of romantic relationships in the mass media. Myths have socialised society through the ages (Vande Berg, Wenner, & Gronbeck, 1998). They transcend across time from the ancient past in legends, folklores, epics to present day because the morals have universal appeal. Myths can beneficial because it can be a good teaching tool as truths can be communicated through them. However, it can also be detrimental as we can be enslaved by it.

This section discusses RQ2, ‘what are the dominant trends of romantic beliefs and expectations viewers’ have developed through the watching of Korean fantasy dramas?’ To probe this question, Mary-Lou Galician’s (2004) Dr. FUN’s Mass Media Love Quiz was adapted.

The means of the items ranged from 3.4 (Item 1) to 2.04 (Item 9)(see Table 7). The mean for the highest item for romantic beliefs and expectations is - ‘the love of a good and faithful true woman can change a man from a “beast” into a “prince”’ (M=3.4, SD=.932), the second highest mean goes to the item, ‘the right mate “completes you,” – filling your needs and making your dreams come true’ (M=3.33, SD=1.016), followed by ‘there’s such a thing as love at first sight’, (M=3.31, SD=.982). These are the three items found to be more prominent among the participants. Thus, the dominant trends of romantic beliefs and expectations found with Scale 1.

Fifty-five cumulative percent agree that ‘the love of a good and faithful true woman can change a man from a “beast” into a “prince”’ (M=3.4, SD=0.932). Fifty cumulative percent agree that ‘the right mate “completes you” – filling your needs and making your dreams come true (M=3.33, SD=1.016). Forty-three cumulative percent agree that ‘there’s such a thing as love at first sight’, (M=3.31, SD=.982).

The questionnaire that was adapted serves also as a media literacy test on mass media portrayals of romantic relationships. The results of this study shows that the participants are generally neutral on their stance in these love myths. This could also be attributed to the relationship status of the participants who have never been in a relationship - 44% of the sample – thus having no past experiences with relationship expectations to reflect on, or it could also be due to the fact that forty-three cumulative percent of participants agree that Korean fantasy dramas give the wrong message about relationships (see Table 4).

The love myth whereby ‘the love of a good and faithful true woman can change a man from a “beast” into a “prince” is a convention of K-Dramaland, and fifty cumulative percent agree to this item (see Table7) This result proves that indeed, fifty-five cumulative percent of the participants have been socialised by this love myth. Galician’s (2004) prescription to counter this notion is to find a compatible partner who does not need much ‘changing’. Women are most at risk of this love myth because the burden to ‘change’ a man is on the woman instead of the man himself. The man should be responsible for himself to change for the better, and for his own good; the same goes for the women as well.

Moreover, fifty cumulative percent of participants agree to the the love myth ‘the right mate “completes you” – filing your needs and making your dreams come true’. The drawback of this love myth is that it causes individuals to expect one’s partner to satisfy their needs. Realistically, everyone should take charge of their own lives and cultivate their own completeness (Galician, 2004).

This section also discusses RQ2, ‘what are the dominant trends of romantic beliefs and expectations viewers’ have developed through the watching of Korean fantasy dramas?’ To probe this question further, Sprecher & Mett’s (1989) Romantic Belief Scale was adapted to assess the participants’ romanticism ideology. Table 11 presents the mean and standard deviation of items on participants’ romantic beliefs and expectations (Scale 2).

The means of the items ranged from 4.07 (Item 1) to 2.48 (Item 14). The mean for the highest item for romantic beliefs and expectations is ‘I need to know someone for a period of time before I fall in love with him or her’ (M=4.07, SD=.856). The second highest mean goes to the item, ‘I believe if another person and I love each other, we can overcome any differences and problems that may arise’ (M=4.01, SD=0.798). Then, ‘If I love someone, I will find a way for us to be together regardless of the opposition to the relationship’ (M=3.68, SD=.886), followed by ‘If a relationship I have was meant to be, any obstacle can be overcome.’

Delving further into the results, Table 8 indicates that seventy-nine cumulative percent agree that love can overcome any differences and problems that may arise (M=4.01, SD=.798). Seventy-seven cumulative percent agree that they need to know someone for a period of time before they fall in love someone (M=4.07, SD=.856). Sixty-four cumulative percent agree that they will find a way for them to be with their lover regardless of the opposition of the relationship (M=3.68, SD=.886). Sixty-one cumulative percent agree that if the relationship they have was meant to be, any obstacle can be overcome (M=3.6, SD=.953) and as well as that their relationship with their ‘true love’ will be rewarding and fulfilling’ (M=3.53, SD=.797). These items can be categorised under the overarching theme of ‘love overcomes all’. Interestingly, they parallel with the conventions of K-Dramaland resolution of love. It can be said that the result for this section indicates that the dominant trend of romantic belief is that ‘love overcomes all’.

Korean fantasy dramas are encapsulated in the idea that love is predestined and thus love can overcome all obstacles; even in reincarnations. For example, in all three of the most watched Korean fantasy dramas among participants in this research, the female and male protagonists are pre-destined to be with each other, and their love for each other transcends time and triumphs over deaths and reincarnations to be with each other again. According to Lee (2012), Love that is depicted in K-Dramaland is pure, loyal, immutable and undying rather than what it really is - illusive, mutable, and vicarious (Chan & Wang, 2011; Lee, 2012). Lovers adhere to their love adamantly regardless of the unfavourable circumstances. The difficulties of realising love send the message that love is important; the more challenging it is to actualise love, the more the audience longs for the realisation of it (Lee, 2012). If the protagonists were to ever consider giving up on love, the only reason would be for the sake of each other, but eventually at the end of a drama series, their love would be a miraculous resolution of hurdles to their love and their love would be realised (Lee, 2012). Therefore, under this section, it can be said that the dominant trend of romantic beliefs and expectations viewers’ have developed through the watching of Korean fantasy dramas is that ‘love overcomes all’.

CHAPTER 5: Conclusion, Limitation & Recommendation

Conclusion

This study has found that when participants utilised Korean fantasy dramas as a media source to gratify their cognition desires, for diversion, emotional release and social utility, they were socialised a few dominant trends of romantic beliefs and expectations. They have been enculturated and socialised that they can change a man from a “beast” into a “prince”; that the right mate “completes them”- thus filling their needs and making their dreams come true, and that love overcomes all.

This study has also found that participants are able to maintain a critical distance in their viewing, for they were familiar with the typical storylines and conventions of Korean fantasy dramas.

It is worthy to note that media influences are not uniform even though we all share the same mass mediated world because of the way symbols are interpreted differently by different individuals.

Limitations

This study is limited in several ways. As fantasy is a recent genre that is rising in popularity, a scant amount of research has been done; hence the amount of literature on the Korean fantasy drama is limited. There is also a scant amount of research that focuses on what individuals learn about love through the consumption of media (Holmes & Johnson, 2009) and on the effects of mass media on individuals’ romantic beliefs and expectations although one’s romantic relationship is critical to one’s happiness and well-being (Jin & Kim, 2015).

Moreover, participants were bounded by three sets of questionnaires that were adapted from other studies, which limits the study in that there is limited room for amendments on the survey questions to better cater the study. Participants could not provide their own individual responses in the questionnaire regarding their personal views on Korean fantasy dramas. Also, the responses to the questionnaire are subjected to the interpretations of the participants. Nine items measured the ways participants utilise Korean fantasy dramas, another nine measured how idealistic and media literate they are when it comes to love, and fourteen measured on romantic ideology. More varied questions could have been asked as there may be other ways that the participants engages with Korean fantasy dramas, and there may be other areas and insights on romantic beliefs and expectations that could have been probed further.

Also, this study only assess how many Korean fantasy dramas have they watched, and did not assess the length of exposure; whether did they watch every single episode or only a few episodes of the Korean fantasy dramas listed responding to the qualifying factor checklist question. Moreover, this study could not take into account participants’ prior exposure to other media sources or agents of socialisation like novels, films, and other television programs that contributes to the development of participants’ romantic beliefs and expectations.

Given that there results were gleaned from a sample of female tertiary students whose identity and beliefs are still in the forming and morphing, most of whom have not been in a relationship before, much knowledge in these areas still needs to be discovered to further our understanding of the effects portrayals of romantic relationships on Korean fantasy dramas. Apart from that, this study is limited to a hundred female participants only hence the sample size is too small for results to be generalised.

Recommendations for Future Research

To delve into the effects of the consumption of Korean fantasy dramas, future research should consider utilising other quantitative methods of analysing data, like a cross-tabulation analysis by considering factors like relationship status and/or sex. Future research should also consider the qualitative research methods like focus group interviews, semi-structured in-depth interviews; where the research would be extended to male respondents.

Content analysis on the structure of Korean fantasy dramas should be conducted to add on to the literature on K-Dramaland so that future research on Korean fantasy dramas could be tailored more suitably and effectively. A ‘K-Dramaland Romantic Ideals Scale’ should be developed so that future research on romantic beliefs and expectations could be analysed more specifically.

References

(2014, October 14). Man seeks divorce over wife’s obsession with TV show. gbtimes. Retrieved from http://gbtimes.com/china/man-seeks-divorce-over-wifes-obsession-tv-show

(2017, January 17). K-drama Goblin is very popular but very controversial in South Korea. Straits Times. Retrieved from http://www.straitstimes.com/lifestyle/entertainment/k-drama-goblin-is-very-popular-but-very-controversial-in-south-korea

Al-Kalili, J., Perry, P., Baggini, J., Moyes, J., & Wybourne, C. (2012, December). What is love? Five theories on the greatest emotion of all. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/dec/13/what-is-love-fivetheories

Addao, A. (2017, April 23). K-Drama binge starter pack: The best Korean fantasy dramas. Hellokpop. Retrieved from http://www.hellokpop.com/list/k-drama-binge-pack-fantasy/

Bacay, A. (2016, December 30). ‘Goblin’ Ep 9 recap and news: Gong yoo sweeps fashion industry with trendsetting outfits in Korea. Inquisitr. Retrieved from http://www.inquisitr.com/3838833/goblin-ep-9-recap-gong-yoo-sweeps-fashion-industry-with-trend-setting-outfits/

Baek, B.Y. (2014, December 26). ‘My Love from the Star’ named top television program of 2014. The Korea Times. Retrieved from http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/culture/2015/01/201_170604.html

Baran, S.J. (2002). Introduction to mass communication: Foundations, fermet, and future. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Baucom, D., & Epstein, N. (1990). Cognitive-behavioural marital therapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Baucom, D. H., Epstein, N., Daiuto, A. D., Carels, R. A., Rankin, L. A., & Burnett, C. K. (1996). Cognitions in marriage: The relationship between standards and attributions. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 209-222.

Berger, A. A. (2014). Media and communication research methods: An introduction to qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). New York: Sage

Bradbury, T., & Fincham, F. (1987). Affect and cognition in close relationships: Toward an integrative model. Cognition and Emotion, 1, 59-76.

Carveth, R., & Alexander, A. (1985). Soap opera viewing motivations and the cultivation process. Journal of Broadcasting Electronic Media, 29, 259 -273.

Chan, B., Wang, X. (2011) Of prince charming and male chauvinist pigs: Singaporean female viewers and the dream-world of Korean television dramas. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 14(3), 291-305. doi:10.1177/1367877910391868

Creswell, J. W. (212). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research, Boston, MA: Pearson

Crossman, A. (2017, March 2). Understanding purposive sampling. Retrieved from: http://sociology.about.com/od/Types-of-Samples/a/Purposive-Sample.htm

Dominick, J.R. (2013). The dynamics of mass communication: Media in transition. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Doo, R. (2017, January 5). Korean drama ‘Goblin’ popular but controversial. Asia One. Retrieved from http://news.asiaone.com/news/showbiz/korean-dram-goblin-popular-controversial

Ferrer, R. (2016, December 6). Gong Yoo’s drama ‘Goblin’ breaks TV popularity record; beats ‘Legend of the Blue Sea,’ ‘Descendants of the Sun’. Yibada. Retrieved from http://en.yibada.com/articles/177265/20161206/gong-yoo-goblin-tvn-legend-of-the-blue-sea-descendants-of-the-sun.htm

Fink, A.S., & Galician, M.-L. (1996). Love or marriage: Television soap opera usage and the construction and cultivation of viewers’ attitudes about romantic relationships. Paper presented at the annual meeting of The Organization for the Study of Communication Language, and Gender, Monterey Bay, CA.

Fry, A. (2015, September 8). Six of the best from Korea. Drama Quarterly. Retrieved from http://dramaquarterly.com/six-of-the-best-from-korea/

Galician, M. –L. (2000). Realistic Romance®. Retrieved from http://www.realisticromance.com/index.html

Galician, M. –L. (2004). Sex, love, and romance in the mass media. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Gottman, J. (1999). Seven principles for making marriage work. New York, NY: Crown.

Hassan, B. (2015). Applying uses and gratifications theory to acceptance of ERP systems.

Hefner, V., & Wilson, B. J. (2013). From love at first sight to soulmate: The influence of

romantic ideals in popular films on young people's beliefs about relationships. Communication Monographs, 80(2), 150-175.

Hendrick, S. S., & Hendrick, C. (2002) Linking romantic love and sex: development

of the Perceptions of Love and Sex Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19, 361-378.

Herzog, H. (1944). What do we really know about daytime serial listeners? In P.F. Lazarsfeld (ed.), Radio Research 1942-3 (pp. 2-23). London: Sage.

Hetsroni, A. (2012). Associations between television viewing and love styles: An interpretation using cultivation theory. Psychological Reports, 110(1), 35-50.

Ho, C.H. CHH. (2013). The analysis of the effects of love values in Korean dramas on Taiwanese viewers--from the perspective of business. Research Papers. Paper 384. Retrieved from http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/384

Hogarth, H. K. (2013). The Korean Wave: An Asian Reaction to Western-Dominated Globalization. Perspectives on Global Development and Technology, 12(1-2), 135–151. doi:10.1163/15691497-12341247

Holmes, B.M. & Johnson, K.R. (2009). Where fantasy meets reality: Media exposure, relationship beliefs, and standards and the moderating effect of a current relationship. Social Psychology: New Research. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Hsu, H. (2012). Korean TV soap operas in Taiwan: An investigation of consumers’ clothing purchase behavior. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 4(3), 16–30. doi:10.5539/ijms.v4n3p16

Iwabuchi, Koichi. (2008). When the Korean Wave meets resident Koreans in Japan: Intersections of the transnational, the postcolonial and the multicultural. In Chua Beng Huat and Koichi Iwabuchi (Eds.), East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave. pp. 243-64. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Jiang, Q., & Leung, L. (2012). Lifestyles, gratifications sought, and narrative appeal: American and Korean TV drama viewing among Internet users in urban China. The International Communication Gazette, 74, 159- 180.

Jin, B., & Kim, J. (2015). Television drama viewing and romantic beliefs: Considering parasocial interaction and attachment style. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 5(10), 51-60.

Joyrich, L. (1996). Reviewing reception: Television, gender, and postmodern culture. Bloomington, Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press.

Jung, S. (2010). Chogukjeok pan-East Asian soft masculinity: Reading boys over flowers, coffee prince and shinhwa fan fiction. In D. Black, S. Epstein, & A. Tokita (Eds.), Complicated currents: Media flows, soft power and East Asia (pp.1-8). Melbourne: Monash University ePress.

Kamini, R.S. (2016, January 13). Why Malaysian couples got divorced. The Rakyat Post. Retrieved from http://www.therakyatpost.com/life/wellness/2016/01/13/why-malaysian-couples-get-divorced/

Katz, E., Blumler, J., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). Utilization of mass communication by the individual. In J.Blumler & E. Katz (Eds.), The uses of mass communication: Current perspectives on gratifications research (pp. 19–34). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Kwon, D. H. (2006). Is it too early to talk about “Hallyu” in the Philippines? Koreanovela and its reception among Filipino audience. Cultural Space and Public Sphere in Asia (pp. 257-288). Seoul: Asia's Future Initiative.

Lakshiny. (2016, February 2). Divorce statistics show that work is getting in the way of marriage – Here’s how you can save yours before it’s too late. Malaysian Digest. Retrieved from http://www.malaysiandigest.com/features/592741-divorce-statistics-show-that-work-is-getting-in-the-way-of-marriage-here-s-how-you-can-save-yours-before-it-s-too-late.html

Lasswell, H.D. (1948). The structure and function of communication in society. In L. Bryson (Ed.), The communication of ideas. New York: Harper.

Lee, G. (2017, May 9). “Produce 101 season 2” takes no. 1 spot in content power index rankings for 4 consecutive weeks. Soompi. Retrieved from https://www.soompi.com/2017/05/09/produce-101-season-2-takes-no-1-spot-content-power-index-rankings-4-consecutive-weeks/

Lee, J.Y. (2014, March 24). YSL gets free ride on drama sensation. The Korea Herald. Retrieved from http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20140324001347

Lee, S. (2012). The structure of the appeal of Korean wave texts. Korea Observer, 43(3), 447 – 469.

Lee, S.J. (2011). The Korean wave: The Seoul of Asia. The Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, 2(1), 85-93.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extension of man. New York: McGraw-Hill

McQuail, D. (1983). Mass Communication Theory (1st ed.). London: Sage

Miyose, C. Y. (2015). Unrealistic weeds of love and romance: Korean drama and the "flower boy" genre. UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. Paper 2390.

Mokwape, M. (2017, February 14). 2016: The worst year for marriage. Mmegionline. Retrieved from http://www.mmegi.bw/index.php?aid=66602&dir=2017/february/14

Mori, Y. (2008). Winter Sonata and cultural practices of active fans in Japan: Considering middle-aged women as active agents. In Chua Beng Huat and Koichi Iwabuchi (Eds.), East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave.pp. 127- 42. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press

Ooi, T.L.H. (2014). The effects of Korean wave on young women’s perception of romantic relationships. Academia. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/22441455/The_Effects_of_Korean_Wave_on_Young_Women_s_Perception_of_Romantic_Relationship

Osborn, J. L. (2012, September 11). When TV and marriage meet: A social exchange analysis of the impact of television viewing on marital satisfaction and commitment. Mass Communication and Society. 15(3), 739 – 757. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2011.618900

Perse, E.M. (1986). Soap opera viewing patterns of college students and cultivation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 30, 175 – 193.

Perse, E.M., & Rubin, A.M. (1988). Audience activity and satisfaction with favourite television soap operas. Journalism Quarterly, 65, 368 – 375

Petty, R.E., & Cacioppo, J.T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion, In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 123 -205). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Reizer, A., & Hetsroni, A. (2014). Media exposure and romantic relationship quality: A slippery slope? Psychological Reports: Relationship & Communications, 114(1), 231 – 249.

Reynolds, J. (2014, August 26). Hollywood’s relationship myths can wreak havoc on real-life romance. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from http://www.chicagotribune.com/lifestyles/sc-fam-0826-romantic-myth-20140826-story.html

Røsand, GM.B., Slinning, K., Røysamb, E., & Tambs, K. (2014). Relationship dissatisfaction and other risk factors for future relationship dissolution: a population-based study of 18,523 couples. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 49(1), pp 109 - 119. doi:10.1007/s00127-013-0681-3

Rubin, A.M. (1985). Uses of daytime television soap operas by college students. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 29, 241 – 258.

Ruslan, N., & Latif, S. S. A. (2016). Malay women readings of Korean drama. Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 4, 343-365.

Schulze, M. (2013). Korea vs. K-dramaland: The culturalization of K-dramas by international fans. ACTA Koreana,16(2), 367 – 397.

Sekaran, U. (2006). Research methods for business 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons.

Serie, K. (2017, February 17). Law firm’s divorce calls double around Valentine’s Day. WHSV 3 abc. Retrieved from http://www.whsv.com/content/news/413949913.html

Severin, W. J., & Tankard, J. W. (2001). Communication theories : origins, methods, and uses in the mass media. New York, NY : Longman, c2001.

Shaver, P., Hazan, C., & Bradshaw, D. (1988). Love as attachment: The integration of three behavioral systems. In R. J. Sternberg & M. L. Barnes (Eds.), The psychology of love (pp. 68-99). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Simpson, J. A., Fletcher, G.J.O., & Campbell, L. (2001). The structure and functions of ideal standards in close relationships. In G. J. O. Fletcher & M.S. Clark (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology: Interpersonal processes. London, UK: Blackwell. Pp. 86-106.

Sprecher, S. & Metts, S. (1989). Development of the ‘Romantic Belief Scale’ and examination of the effects of gender and gender-role orientation. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 6, 387-411.

Sternberg, R.J. (1987). Liking versus loving: A comparative evaluation of theories. Psychological Bulletin, 102, 331-345.

Sternberg, R. J, (1998). Cupid’s arrow: The course of love through time. New Yokr: Cambridge University Press.

Vande Berg, L.R., Wenner, L.A., & Gronbeck, B.E. (1998). Critical approaches to television. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Vannelli, A. (2017, January 7). South Korean drama 'Goblin' controversies - male lead as a god, big age gap in relationship and over product placements. Yibada. Retrieved from http://en.yibada.com/articles/184215/20170107/south-korean-drama-goblin-tvn-lee-dong-wook.htm#ixzz4WzNrBYsx

Vu. H.T., & Lee, T. (2013). Soap operas as a matchmaker: A cultivation analysis of the effects of South Korean TV dramas on Vietnamese women’s marital intentions. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 90(2), 308 – 330. doi:10.1177/1077699013482912

Wilson, J.R., & Wilson, S.R. (2001). Mass Media/mass culture: An introduction. New York: McGraw Hill.

Wimmer, R. D. & Dominick, J. R. (2014). Mass media research: An introduction (10th ed.). US: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Yang, J. (2012) The Korean Wave (Hallyu) in East Asia: A comparison of Chinese, Japanese and Taiwanese audience who watch Korean TV dramas. Development and Society, 41(1), pp.103-147. Retrieved from: http://isdpr.org/isdpr/publication/journal/41_1/05.pdf

Zurbriggen, E.L & Morgan, E. (2006). Who wants to marry a millionaire? Reality dating television programs, attitudes toward sex, and sexual behaviours. Sex Roles, 54(1/2). doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-8865-2

Comments